With the help of a gift from the Spiller family, we have started to digitize “nowhere else to be found” materials through a local and global resource company, Hein Online. These illustrate congregational, community and international history found within the Museum, that would otherwise be difficult to access, especially within the older and bound volumes. All of these materials connect to member history, and provide genealogical resources to explore. Check out the Hein Online link above!

All of us are responsible for one another

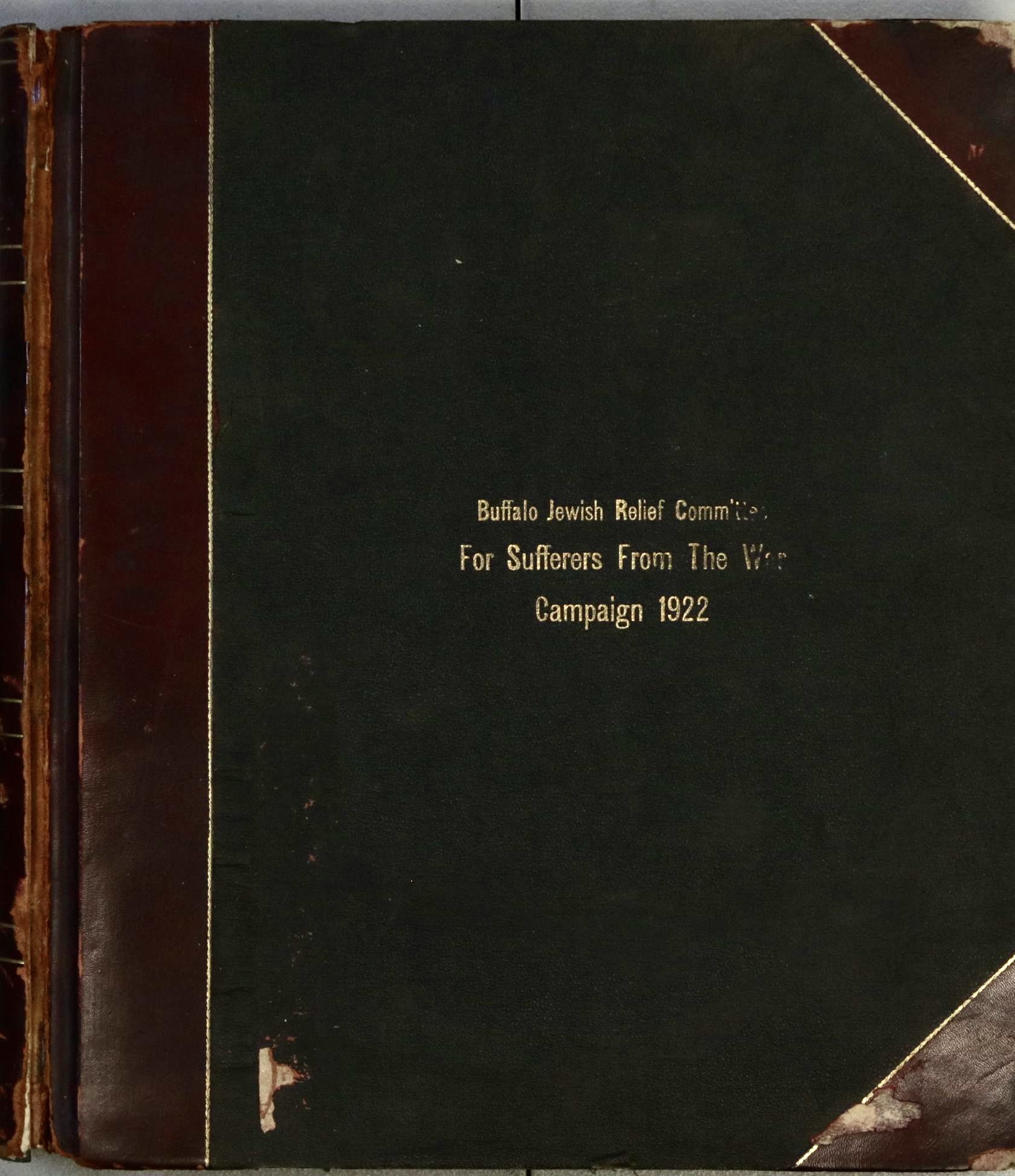

With the old adage in mind, “Never judge a book by its cover,” we begin with an unassuming ledger that is now over a century old. “The Buffalo Jewish Relief Committee for Sufferers from the War, Campaign 1922,” reveals how Temple Beth Zion members led the way for the entire community, Jews and non-Jews to help aid European Jewry after WWI

.

The Russian Revolution had shaken eastern Europe in 1917, and violence and the threat of violence embroiled the region as different national groups fought for independence throughout the early 1920s. In the meantime, while the Great War had ended in 1918, many aspects of the “peace” remained unfinished: treaties were under negotiation, and interests, such as minority rights, still needed resolution. This remained a time of intense violence, and for Jews a period of pogrom, mass starvation and disease, as typhus decimated communities already under attack. This was also the period in which the flu pandemic killed millions across the globe, not just in Europe but also here in America.

In the past, Jews had left Europe in times of violence and famine and had emigrated to America. But the year of the ledger is significant. It is around the same time that anti-immigrant feeling was gaining an upper hand in America. The year before this 1922 campaign, the Emergency Quota Act (1921) set immigration limitations based on different national groups that impacted eastern European prospective immigrants more harshly. (The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 would lower those numbers still further). This was the backdrop in which this ledger comes into its meaning.

Eugene Warner of Temple Beth Zion, and community leader, was appointed statewide coordinator of the campaign. He was aided by anther Temple Beth Zion member, Cecil Wiener, a champion for immigrants in Buffalo, alongside leaders of other synagogues and volunteers from across the community. The Buffalo campaign had a target of $150,000, but it went “over the top,” exceeding its goal and raising $165,000 (almost $3 million in today’s dollars). At the end of an intense period of fundraising, a partial list of donors was published (Buffalo Jewish Review, Feb 10, 1922, pp. 14, 19). By the close of the campaign over 3000 had donated what they could. Later the fundraising knowledge gained by organizers and volunteers enabled them to raise money for the aid of German-speaking Jewish refugees in the 1930s.

What else does this ledger tell us? It gives us family names that are recognizable as part of Temple Beth Zion descendants. It demonstrates that fundraising is accretionary, and that every dollar counts, literally from $1 to $500. It gives us the names of Jewish organizations that were active at the time. It even allows for gender analysis as married women are sometimes listed by their own first name, rather than solely by their husband’s name.

Most of all, it provides a snapshot of where Jews lived in Buffalo at the time. Each donor name includes an address, left out of the published list in the Buffalo Jewish Review. Some are business addresses, but this makes up a minority of listings. By reading through the home addresses (and sometimes their changes within a few months), we see the beginnings of a northward move in Buffalo, as well as a still strong showing on the East Side and in the streets around Delaware Avenue. There is also a residential trend to the West Side and Humboldt. It illustrates a community of subcommunities mixing and growing as the boundaries between older founding communities of Buffalo Jews, and newer immigrant descendants becomes a lot more fluid. It allows us to see older areas of living and new choices of residence, and it further illuminates the sheer range of neighborhoods Jews chose to settle in.

As a genealogical, geographic, economic and social profile of Buffalo Jewry at a particular moment, it’s a fascinating data trove for all of us to read, and maybe it’s a research project waiting for you to craft?! Please contact museum@tbz.org if you are interested in creating a study. Otherwise, Happy Reading!

A later essay will provide information about Rabbi Bernard Cantor and his connection to TBZ and European Aid in 1920.